Questionnaire on sleep guidance

Indhold på denne side:

To get a broader picture of the prevalence of counseling in Denmark, Greenland and the Faroes, and practice of, sleep training, we prepared an online questionnaire addressed to parents. As part of the development process, we tested an early version of the questionnaire on a group of parents and psychologists (about 80 people in total), whose feedback led to many changes and improvements.

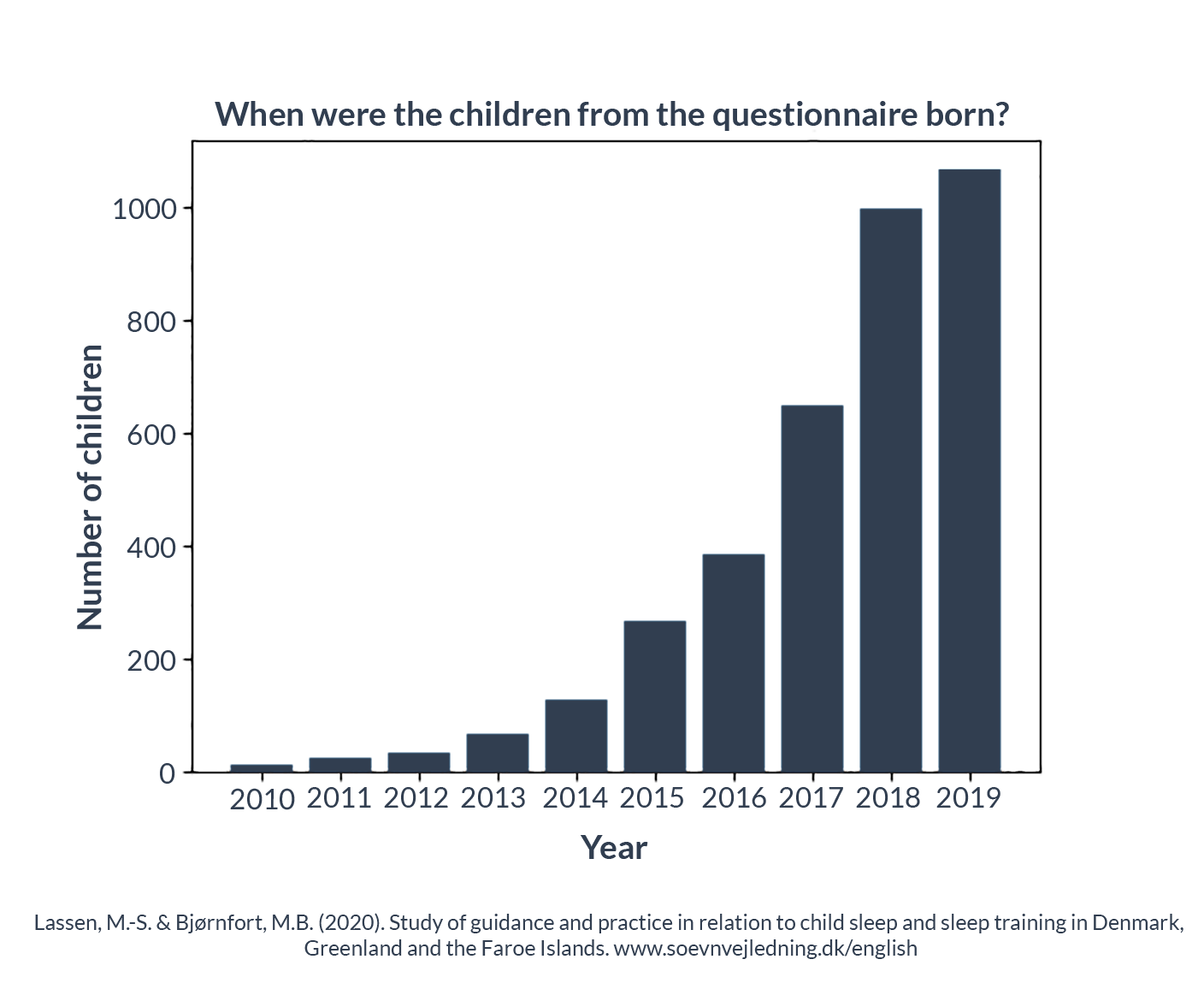

The questionnaire was open for answers between September 22, 2019 and December 31, 2019. During this period, we invited parents to participate in the survey via various social media, and we received 3,627 answers.

The questionnaire was open to parents with children born in 2010 or later, but the vast majority of the responses concerned children born much later. For example, 96% of the responses concerned children born in the period 2014-2019 and 93% children born in the period 2015-2019. In terms of the ability to compare data, responses from parents with children born in 2017-2019 were an important part of the dataset; these years include 2711 responses or 75% of the full dataset.

The questionnaire contained between 12 and 27 questions depending on the respondent’s individual answers, as not all respondents were asked to answer all the questions. For example, if the respondent said no to talking to the health visitor about their child’s sleep and / or putting them to sleep, they skipped the sections that asked about this guidance. We estimated that it would take 3-9 minutes to answer the questionnaire, but we also gave respondents the opportunity to add their own comments and free answers next to the given answer options. Many of the parents made use of this opportunity and these comments in themselves form an important dataset.

There were several cases in which the respondents had used the option of free answers, but at the same time had chosen one of the given answer options, often with additional information. We read all the answers in free form, and where there was a clear reference to an existing answer (e.g. ‘My health visitor’, where the option ‘Health visitor’ already existed, we added the answer manually to the relevant category.

3,580 of the answers to the questionnaire (almost 99%) were given by a parent who identified themselves as the mother of the child, while the rest were divided between fathers or those whose relationship to the child was identified as ‘Other’. When we use the term ‘parents’ is it thus a collective term for both those respondents who identified themselves as such and those who did not.

The proportion of respondents who identified themselves as ‘mother’ reflects that it is most often the mother who is the primary caregiver, especially in the first months of the child’s life, and it is she who will have the most contact with health professionals regarding the child. Although we did not specifically design the study to address mothers, we are still in line with common practice in other parent studies, which typically focus on the relationship between mother and child.

We asked the parents to answer the questionnaire based on their youngest child, although we also asked them for basic information regarding sleep training counseling that they might have received for older children. Many of the questions focused on advice from the health visitor about sleep, but we also asked about advice received from other health professionals, educational staff, family and friends, books and other media. The rationale for emphasizing health visitors is that they are the primary source of information and support for new parents, and the quality of their counseling has the potential to either promote good parental care of and approach to the child or prevent harmful methods from being used or becoming widespread. In addition, the data we have collected regarding the advice from health visitors has made it possible for us to compare with answers to specific questions that we asked the municipal health visitors in a freedom of information request for documents regarding guidance on sleep and sleep training.

Due to the way in which parents were invited to participate, often through Facebook groups and pages for parents, or groups for geographical areas, the responses cannot be considered as a randomized or representative sample of parents in Denmark, Greenland and the Faroe Islands.

A number of parent groups on social media discuss different approaches to parenting, and our questionnaire was shared with several groups with a particular interest in ‘natural’ and ‘attachment-focused’ parenting. It is therefore likely that our dataset includes a good deal of responses from parents who discovered the questionnaire through these groups. However, our questionnaire is designed to inquire into factual information and experiences, minimizing bias from respondents’ personal opinions and attitudes. One source of bias that is harder to counteract comes from the fact that our questionnaire was based on voluntary participation. ‘Voluntary Response Bias’ is a well-known phenomenon, leading to an over-representation of respondents who (in the case of our questionnaire) have had ‘strong’ experiences that they feel a particular desire to share. This may be the case, for example, with the many respondents who spent extra time writing often long free-text comments, sharing details from their experiences and describing how these had impacted their lives. These answers are, of course, valid, but we must be careful not to treat the frequency or number as an indication of the experiences of the general population.

Collecting a statistically reliable dataset would require a fully randomized trial that took into account a wide range of factors – and this is currently beyond the scope of our work and resources. Nevertheless, the results of the current questionnaire survey raise sufficient concern to support action at municipal and national level without the delay that further data collection would entail.

In interpreting the study results, our definition of ‘sleep training’ is important. We asked the parents if they had received different types of advice on helping their child sleep. The questions we asked covered a range of advice, from sensitive response to delayed and minimized response from parents including the most far-reaching forms of sleep training in the form of ‘cry it out’ where the child cries alone without parental contact. Our questionnaire did not contain definitions of sleep training and Cry it out, and we did not ask the respondents directly if they had received this type of advice, as this could have affected their answers in different ways, introducing bias, false positive or false negative responses and priming. The questions were therefore designed to examine various elements that incorporate these techniques in as neutral a manner as possible, and we considered combinations of the responses after submission to determine whether the advice received should be considered as a type of sleep training.

The questionnaire survey was structured in a way that made it possible to differentiate between different forms of sleep training: one in which the parents were instructed to leave the child, even if it was dissatisfied or complaining after it was tucked in – and one in which the parents were instructed in leaving the child even if he or she cried (so-called ‘cry it out’ or CIO). Both of these forms of sleep training were considered potentially harmful in the interpretation of the results.

Many of the numbers in the results and the summary from the questionnaire responses have been calculated using a combination of responses. The software we used to analyze the dataset ensures that an answer cannot be counted more than once. However, this may mean that the figures obtained at first glance may look incorrect. For example: 100 people may have answered ‘Yes’ to question A, and 100 answered ‘Yes’ to question B, but the number who answered ‘Yes’ to either A or B can be as low as 100 (if they are the same people) or as high as 200 (if no one answered ‘Yes’ to both answers). As a rule, the total number is somewhere in the middle.

If the respondents moved municipality during the time period covered by the questionnaire, we asked the respondents to specify the municipality where they received the sleep advice mentioned in their response. We did this to ensure proper registration of the municipalities where the different types of sleep advice were given.

All 98 municipalities in Denmark as well as the Faroe Islands and Greenland are represented in our survey, although the number of respondents varies greatly between the different municipalities, the Faroe Islands and Greenland. A full third of the respondents (1,220 in total) were from 4 municipalities (Copenhagen, Aarhus, Aalborg and Odense), and the median number of responses per Danish municipality, the Faroe Islands and Greenland is 18.5 for the full dataset and 13 for the period 2017- 2019.

Unless otherwise stated, the statistics in the following sections are taken from the 2,711 responses we received regarding children born in 2017 or later (the most recent were in 2019, when the questionnaire was closed). The places where we have used the full dataset with 3,627 responses from parents with children born between 2010-2019 are identified in the text. This is done to better compare with data collected from our freedom of information requests to the municipalities, which only covered the years 2017-2019, as well as to provide a clearer picture of recent practice in sleep counseling and avoid potential problems of including data which may no longer be relevant for the assessment of the current situation.

Occurrence of sleep training advice

Although our questionnaire also asked questions about various types of sleep training guidance from the health visitor to get an overview of the sleep training guidance provided by the public sector, our primary focus was on cry it out sleep training, which is considered to be the most severe form of sleep training.

Out of the 2,711 responses from parents to children born in 2017-2019, 42% of these (1135) had been recommended cry it out; 312 had received this type of advice from at least one professional, 145 had received it from a health visitor and 1016 had received the recommendation from their personal network, such as friends, family, colleagues or mothers’ groups. A further 332 parents who had not received recommendations for cry it out sleep training from professionals or their personal networks had read books, articles, etc. about cry it out and / or had encountered recommendations from social media. This means that 54% of the parents from the questionnaire with children born in 2017-2019 have been exposed to cry it out sleep training in some form.

Definition of sleep training and cry it out in connection with the questionnaire sent out.

In connection with the preparation and analysis of the questionnaire for parents, we have used two sets of criteria for sleep training and cry it out sleep training.

‘Sleep training’ is defined as guidance that instructs parents to leave the child when he or she is tucked in, even if he or she is dissatisfied, complains, yells, calls or otherwise exhibits signaling behavior about the need for or desire for contact – including crying.

‘Cry it out’ (CIO) is defined as guidance that instructs parents to leave the child, even if it cries or screams when it is tucked in. The child’s crying and / or screaming is ignored. The parents can either ignore the child for shorter or longer intervals or indefinitely.

Cases of cry it out are thus part of the numbers for sleep training, while the numbers for cry it out only include leaving a child crying or screaming when he or she has to sleep.

Our questionnaire only looked at these two versions of sleep training.

Should the questionnaire have captured all editions of sleep training, as described in our overall definition of sleep training, the questionnaire would have contained many more questions, which would have entailed a considerable risk of dropout among the respondents.

The criteria are also adapted to the possibility of comparing the results of the questionnaire with the freedom of information requests for documents concerning the municipalities’ guidance on, recommendation of and knowledge about sleep training.

According to Statistics Denmark, the birth rate for the whole of Denmark is a little over 61,000 children a year – and although we must be careful to treat our dataset as being representative of the entire population, even a much lower incidence of advice on cry it out sleep training than we observed in our study would mean that thousands of children and their parents receive this outdated and potentially harmful advice every year.

When we look at the sources of the advice on sleep training, we see the following:

Source of advice on cry it out sleep training | Number of respondents |

|---|---|

Non-personal sources (books, articles, social media) | 887 |

Friends, family, mothers’ groups and non-professionals | 1016 |

Health- and childcare professionals | 312 |

Personal contact (professional and non-professional) | 1135 |

All sources combined | 1467 |

Note that the total figures are less than the sum of their respective categories, as many respondents reported several sources of advice on cry it out sleep training. This, combined with a high number of respondents who reported advice from non-professional and so-called ‘non-personal’ sources (e.g. books, articles, etc.), illustrates how widespread counseling in cry it out sleep training is in society. This advice on cry it out is exchanged between people in the community apparently without much criticism and even comes from, among others, health professionals and books, without critical reservations.

In order to reduce the prevalence of counseling in cry it out sleep training, action is required that addresses all of these potential sources of misinformation.

The results also show that health professionals and pedagogical staff generally advise less on cry it out sleep training than other sources. Of those of our respondents who had received counseling in cry it out sleep training, 27% had received at least some of the counseling from a professional. This is a worryingly high number, and it is also important to take into account that parents may be more likely to follow the advice of a professional. In addition, professionals have an important role in preventing misinformation and raising general awareness of the potential harmful effects of cry it out sleep training in society.

Our respondents have received cry it out sleep guidance from the following occupational professionals:

- Health visitor (public and private)

- Nursery and kindergarten teachers and assistants

- Childminder/Daycare in private home

- Doctor in General Practice

- Sleep Coach

- Hospital Doctor

- Midwife

- Occupational Therapist

- Physical therapist

- Family Supervisor or Family Therapist

- Chiropractor

- Psychologist

- Nurse

- Unspecified professional

The diagram below illustrates how these instances are attributed to the different professional groups:

When we look at the different professions and how many of our respondents received advice on cry it out sleep training from them, it is clear that health visitors are the most common source of this kind of advice to the respondents. This does not mean that advice from health visitors is generally of lower quality than that from other professionals – after all, only 7.6% of respondents with children born in 2017 or later received advice on sleep training from their health visitor, and only 5.3% received guidance on cry it out sleep training from their health visitor.

It is important to remember that many parents answered the questionnaire while their children were still very young: Almost half of our dataset (with children born in 2017-2019) dealt with children under the age of 1 at the time of completing the questionnaire, and 1 in 6 (16%) were under 6 months. We therefore assume that some of the parents who had not yet received guidance on sleep training when answering the questionnaire may have received such advice after answering our questions.

If we look at the full dataset, which includes children born before 2017, we see a slightly higher incidence of sleep training guidance from health visitors (9.8% for all types of sleep training and 7.5% for cry it out sleep training alone) . Similarly, we see that 16.5% of the full dataset received guidance on sleep training from a professional: a figure that drops to 13.4% when we only look at children born in 2017 and later.

The reason that health visitors are the most common source of professional guidance on sleep training, despite the fact that their guidance accounts for only a small percentage of all cases of guidance on sleep training, is that health visitors have an important role as a primary source of information and conversations about infant care. At the same time, they are more likely to be in contact with parents several times. The other major professional sources of counseling for cry it out sleep training included educational staff such as day care workers, nursery and kindergarten teachers and assistants, doctors in general practice, and sleep coaches

These results are not limited to a few parts of the country. With a conservative estimate, we have identified 82 out of 100 geographical areas (Danish municipalities as well as the Faroe Islands and Greenland) where the parents lived as they received professional advice on cry it out sleep training, when we count all different professions. It is likely that we would have identified even more with a larger number of respondents. For example, we know (via freedom of information requests to the municipal health visitors) of 2 municipalities that have provided advice on cry it out sleep training, but where this has not been captured in the questionnaire.

Due to the important role of health visitors in communicating various sleep advice about child sleep and warning against potentially harmful sleep advice, as well as due to their frequent and prolonged contact with parents, and the impact this has on families, our study has a special focus on guidance from health visitors. This additional information, obtained through specific sections of the questionnaire, allows us to go into much more detail with the sleep counseling provided by health visitors.

Sleep counseling from health visitors

The answers from our questionnaire do not point to a specific subgroup of parents who are more likely to get sleep counseling advice from their health visitor. Rather, there is a small but significant probability of receiving this type of counseling in the child’s first 9 months, which is broadly similar across children’s age group and geographical regions.

The questions we asked about the advice of health visitors give us the opportunity to distinguish between different degrees of sleep training.

For example, we asked the following two questions:

- Did the health visitor advise you that your child is allowed to be unhappy or complain when it is tucked in?

- Did the health visitor advise that your child is allowed to cry when it is tucked in?

(Italics are added in this article to show the difference between the two questions, but it did not appear in italics in the questionnaire.)

If the answer to one of these questions was ‘yes’, we continued to ask: “Were you to stay with the child or go somewhere else when your baby was tucked in? ”

144 of our respondents were advised to leave their crying child (cry it out or CIO) – and our focus in this section will for the most part be on this severest form of sleep training.

We have identified that the health visitors in the years 2017-2019 have recommended cry it out sleep training in 67 out of the 100 surveyed geographical areas, which were the 98 Danish municipalities as well as Greenland and the Faroe Islands. 63 of these were identified in the questionnaire, a further 2 came solely from our freedom of information requests to the municipalities and 2 came from reading their websites. This is a conservative estimate and a larger number of respondents would probably increase this number. When we take the full dataset for children born in 2010-2019 and combine it with answers from the freedom of information requests, we have reports that health visitors have recommended cry it out sleep training in 82 of the geographical areas (Danish municipalities as well as the Faroe Islands and Greenland).

We received responses from 49 parents who told us that their health visitor had recommended that they read one or more of the following books / pamphlets on the cry it out method:

- “Det Lille Barns Søvn” (“The small child’s sleep”) (Libero)

- “Godnat og sov godt: Lær dit barn gode sovevaner” (“Duérmete, niño” (Sleep, Child. red.))(Eduard Estivill & Sylvia de Béjar)

- “ Twelve Hours Sleep by Twelve Weeks Old ”(Suzy Giordano)

These 49 parents are included in our total number of parents who have received guidance on cry it out sleep training.

A further 8 parents were recommended one or more of a selection of more general books that include cry it out among other topics. Apart from a single one of these, who had also received other cry it out guidance, these are not counted as cry it out advice from the health visitor, although they arguably could have been.

It seems that there is no lower limit for the age of children whose parents are advised to use some form of sleep training. 93% of respondents who received advice about sleep training, and who told us their child’s age when the instructions were given, received this advice when the child was 9 months or younger. This is not surprising given that the majority of contact between parents and health visitors takes place when the child is very young. However, we find it worrying that 31% of cases occurred when the child was 3 months or younger. If we only look at advice on cry it out – the most serious form of sleep training – the numbers do not look very different. Here, 25% of those who received counseling in cry it out received this counseling while the child was 0-3 months old. This is particularly problematic as it is assumed that crying it out has more serious consequences the younger the child is.

In most cases (approx. 76%) health visitors who advised cry it out did not specify a maximum time limit for how long the child should be allowed to cry alone at a time. In cases where the health visitor indicated a time limit for crying, the most common recommendation was up to 1-3 minutes. However, the parents also described cases where they had been instructed to let the child cry for up to several hours, and one respondent replied: ‘Until she cried herself to sleep‘.

This pattern is repeated across all age groups: even for children aged 0-3 months, approximately 74% of cry it out advice was given without a time limit, and 73% of the sleep training, where the child was unhappy or complained alone, also had no time limit.

Some parents wrote in comments that they were expected to do it as long as they could endure it and others that it was about the nuances of crying. Some were also told that it was up to their own judgment.

These methods risk harming the baby, even if there is a time limit on how long you are to let the baby cry.

One group that we focused on in particular was first-time parents, as they are probably those most likely to seek advice on children’s sleep.

In addition, it is reasonable to assume that they are more receptive to questionable advice due to their relative lack of experience. Based on the answers to the questionnaire, we found no significant difference in the probability of receiving recommendations for sleep training depending on whether it was the parents’ first or later children. In order for a child to be exposed to sleep training, it naturally requires that the parents follow the advice on sleep training, which may well depend on previous experience with older children.

Experiences and results with sleep training methods

To evaluate how many people tried to follow the instructions on sleep training, and their experiences, we included the full dataset with 3,627 answers, which includes children born before 2017. This gives a larger number of respondents (and therefore more meaningful statistics), and it is reasonable to assume that the psychological reactions of children and parents to sleep training have not changed much during this period. Statistics in this section are taken from the full dataset.

Our questionnaire only asked the respondents if they followed the advice on sleep training, and their experience with the sleep training, if this advice came from their health visitor. We therefore have a relatively small number of responses from which to draw conclusions, and these figures are therefore not an indication of the prevalence of attempts to sleep train in the general population, where many are advised to sleep train by sources other than their health visitor.

There is no statistically significant difference between the answers for cry it out counseling and the answers for other forms of sleep training in our study, which is why the numbers are added together in this part of the analysis. We received responses from 140 parents who had tried to sleep train their child after being advised to do so by their health visitor. 138 of these respondents chose to tell us the age of the child when this advice was given.

From the distribution of these ages, it can be seen that most cases involved babies aged 6 months or younger:

Age | Number of respondents |

|---|---|

0-3 months | 34 (25%) |

4-6 months | 48 (41%) |

7-9 months | 31 (22%) |

10 months or older | 16 (12%) |

A startling observation regarding the number of parents who followed the advice on sleep training from their health visitor is that there is a big difference in the number of first-time parents and repeat parents, respectively. First-time parents had a 46% probability of following sleep training advice from their health visitor, while this figure was “only” 22% for repeat parents. In other words, first-time parents are more than twice as likely to follow sleep training advice from health care providers compared to repeat parents.

We asked the parents who had tried sleep training to tell us whether they completed the process and achieved the desired result, that the child could fall asleep on its own and sleep alone.

There are a number of reasons why a sleep training program may not be ‘completed’ – or rather stopped before the child learns to sleep without crying or complaining. It may be that the child’s behavior does not change in the desired way, or that the parents decide to stop the process before the desired effect is achieved. When we compare the numbers for those who completed sleep training of their child with those who tried but stopped, we see that only 41 out of 140 completed the sleep training with the desired result. This represents a successful implementation rate of 29%, which is far from impressive, especially for methods that can have so many potential adverse effects. It is very possible that some of these children would have developed the ability to sleep alone without sleep training [1] , and it is not guaranteed that even these ‘success stories’ resulted in the permanent acquisition of the child’s ability to fall asleep on its own and sleep alone. In addition, research has shown that parents often need to repeat the sleep training at different intervals to maintain the desired sleep behavior [2] . Of course, we must again remember that our study did not use a randomized sample of the population, but nevertheless it is extremely difficult to explain the difference between the proportion of parents who completed sleep training with the desired result, and the expectations and promises often cited for these methods, purely with reference to the composition of our respondents.

One of the main reasons for the difference in apparent success- and completion rate between our study and many other studies is that authors who promote sleep training typically only include the success rate among families who ‘complete’ the sleep training program fully and do not count those who stopped the process early because, for example, it was too traumatic for the child or parents. For example, a 2006 review article found that 94% of sleep training studies show a positive effect [3]. Most studies of sleep training thus find positive results, but these results will inevitably be characterized by the fact that only families who complete the sleep training are counted in the study. There is often a high drop-out rate in studies of sleep training, and this results in a measurement error, as those parents who do not achieve the desired effect and / or do not like the method are more likely to drop out.

In addition, in our questionnaire, we deliberately do not describe stopping sleep training, failing to complete the guided sleep training, or responding to the child’s needs as something “wrong” or bad. We hope that our neutral language allows parents to answer our questions with minimal bias.

The two main arguments that supporters of sleep training use to support their case are that their methods are not harmful and that they are effective. The basic research in children’s development and attachment theory shows the potential harmful effect of sleep training, which contrasts with this first argument. Our indications of poor success rates also indicate reason to challenge the second argument.

Cultural expectations when children need to sleep

In addition to what the dataset can tell us about counseling in the specific forms of sleep training we looked at, it also contains information that either relates to sleep training methods (or parts of them), or that illustrates other widespread issues concerning expectations of children’s sleep, and whether there is a cultural focus on contact or separation between parent and child when the child needs to sleep.

A good example of expectations in connection with the child’s sleep is about the child’s signals in connection with the child’s sleep.

A good example of expectations in connection with the child’s sleep concerns the child’s signals in connection with the child’s sleep.

When we look at this advice in general, we see that the health visitors to a large extent advise the parents that the child may be unhappy, complain or cry in connection with the child having to sleep. 734 parents with children born in 2017-2019 were informed that the child may well ‘complain or be unhappy’, while 907 parents answered that they had not received this advice, and 407 said that their child had not been unhappy or complained when tucked in. For the full dataset, 1046 parents had specifically been told that the child may well be unhappy or complain, while 1160 replied that they had not received this advice. We can therefore see that of the parents for whom this question was relevant, almost half had been told that the child may be unhappy or complain.

In terms of crying, 367 of the parents with children born in 2017-2019 were instructed that the child may well cry when tucked in, while 1353 answered no to this question.

One explanation for the above may be that the health visitors want to reassure the parents who have children who are unhappy at bedtime.

However, it can be problematic to simply categorize children’s dissatisfaction and crying as ‘something children just do at bedtime’ when, as we know, this is children’s way of communicating.

This leads us to a considerable number of respondents (383) answering that the health visitor had led them towards ‘Learning / noticing the difference between whining, protest crying and real crying’, in answer to the question ‘What advice did you get from your health visitor about how you could help your child sleep? ‘.

Of course, listening to and understanding the child’s signals can be good advice and is not in itself problematic. However, the fact that so many parents are told that not all crying is ‘real crying’ and that ‘crying’ is generally expected and common when the child needs to sleep, may normalize sleep training or cry it out, and lead to ‘hidden’ cases.

In order to take a closer look at the question of parent / child contact versus separation-based counseling, it is interesting to analyze the answers to the following questions from the questionnaire:

‘What advice did you get from your health visitor about how you could help your child sleep? Feel free to tick several possible answers. ‘

The set of possible answers was designed as a list of different types of advice that health visitors could have given to help children sleep. The possible answers were presented as a list without any context indicating whether we consider them to be a good or bad approach

After receiving the answers, we grouped them into categories and focused in particular on counseling that promotes parent-child contact versus that which promotes separation from the child. The options divided into these categories are as follows:

Contact:

- Giving the child body contact, e.g. by lying next to them, holding hands or letting the child sleep on you

- To breastfeed / bottle-feed the baby to sleep

- To use a baby carrier

- To rock the baby to sleep

Separation:

- To take care not to give the child (bad) habits by e.g. rocking / breastfeeding / bottle-feeding it to sleep

- To teach the child to fall asleep on its own

- To separate food and sleep, i.e. not to breastfeed / bottle-feed to sleep

- To learn / notice the difference between yelling, protest crying and real crying

- That it could be a good idea for the child to sleep in their own room (before 1 year old)

- To stop breastfeeding / bottle-feeding at night (before 9 months)

- To avoid picking up the child once it has been put to sleep

- To stop breastfeeding / bottle-feeding at night (after 9 months old)

- To avoid eye contact once the child has been put to sleep

- To help the child find peace by making sure it does not get up again after it is tucked in

- That it could be a good idea for the child to sleep in their own room (after 1 year old)

There were also other answer options that are not in either of these two categories. Some examples of these are:

- Creating routines and predictability

- To swaddle the child

- Giving the baby a bath before bedtime

We received 975 responses from parents of children born in 2017 or later who had received at least one type of separation-based counseling and no contact-based advice from their health visitor; in contrast, only 299 received at least one type of advice in the ‘contact’ category without also having received separation-based advice. This bias in favour of separation of parent and child remains significant, although comparison with figures from children born before 2017 indicates that there has been a slight change towards more contact-based counseling.

The number of respondents who received only contact-based guidance is represented by the green parts of the bar; those who received only separation-based guidance are represented in pink, and blue is used for those who received a combination of the two. The percentages are displayed in the bars along with the actual number of responses for that category in parentheses, and the data is broken down by whether the children were born before 2017 or not. It can be seen that advice on separation between child and parents is dominant. At the same time, however, a slight apparent improvement is seen over the ten years our questionnaire covers, but a significant majority still receive none of the advice in the contact category.

We can also look at the individual answers that stand in opposition to each other, for example to teach the child to fall asleep on its own versus to give the child physical contact, to see the relative probabilities of being advised in one way or another on these topics:

Likelihood of parents receiving certain advice

To separate food and sleep, i.e. not to breast- or bottle-feed to sleep | 3.2 times more likely than | To breast- or bottle-feed the child to sleep |

To take care not to give the child (bad) habits by e.g. rocking / breastfeeding / bottle-feeding it to sleep | 3,8 times more likely than | To breast- or bottle-feed the child to sleep |

To take care not to give the child (bad) habits by e.g. rocking / breastfeeding / bottle-feeding it to sleep | 3,0 times more likely than | To rock the baby to sleep |

To teach the child to fall asleep on its own | 2,9 times more likely than | To rock the baby to sleep |

To teach the child to fall asleep on its own | 1,5 times more likely than | Giving the child physical contact, e.g. by lying next to them, holding hands or letting the child sleep on you |

To teach the child to fall asleep on its own | 6,4 times more likely than | To use a baby carrier |

To teach the child to fall asleep on its own | 5,4 times more likely than | To use a baby hammock |

To stop breastfeeding / bottle-feeding at night (before 9 months) | 1,6 times more likely than | To breast- or bottle-feed the child to sleep |

At stoppe amning/flaske om natten (efter barnet var fyldt 9 måneder) | 1,3 times more likely than | To breast- or bottle-feed the child to sleep |

To stop breastfeeding / bottle-feeding at night (after 9 months old) | 2,9 times more likely than | To breast- or bottle-feed the child to sleep |

Summary

There is a clear and consistent preference, in all forms of sleep-related counseling, for separation-based counseling over contact-based counseling. This normalizes the idea that children, even at a very young age, should have reduced physical contact with their parents when sleeping.

It is this kind of basic assumption that creates an environment where sleep training can be disseminated and seen as necessary. The need to educate the public and professionals about the potential harmful effects of sleep training should be seen as part of a broader context in which our society has come to regard the child’s separation from its parents as a normal and desirable behavior.

Professionals’ general tendency to regard separation as healthy, natural, and normal results in their guidance on separation.

This should also change.

References:

- Marie-Hélène Pennestri, Christine Laganière, Andrée-Anne Bouvette-Turcot, Irina Pokhvisneva, Meir Steiner, Michael J. Meaney, Hélène Gaudreau, on behalf of the Mavan Research Team. Uninterrupted Infant Sleep, Development, and Maternal Mood. Pediatrics Dec 2018, 142 (6) e20174330;

- Loutzenhiser, L., Hoffman, J., & Beatch, J. (2014). Parental perceptions of the effectiveness of graduated Extinction in reducing infant nightwakings. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology, 32(3), 282-291.

- Mindell, J. A., Kuhn, B., Lewin, D. S., Meltzer, L. J. & Sadeh, A (2006). Behavioral treatment of bedtime problems and night wakings in infants and young children. Sleep, 29(10), 1263-1276.